Latin Funerary Inscriptions | Epitaphs for Women

Agileia Prima

By Elisabeth Campbell

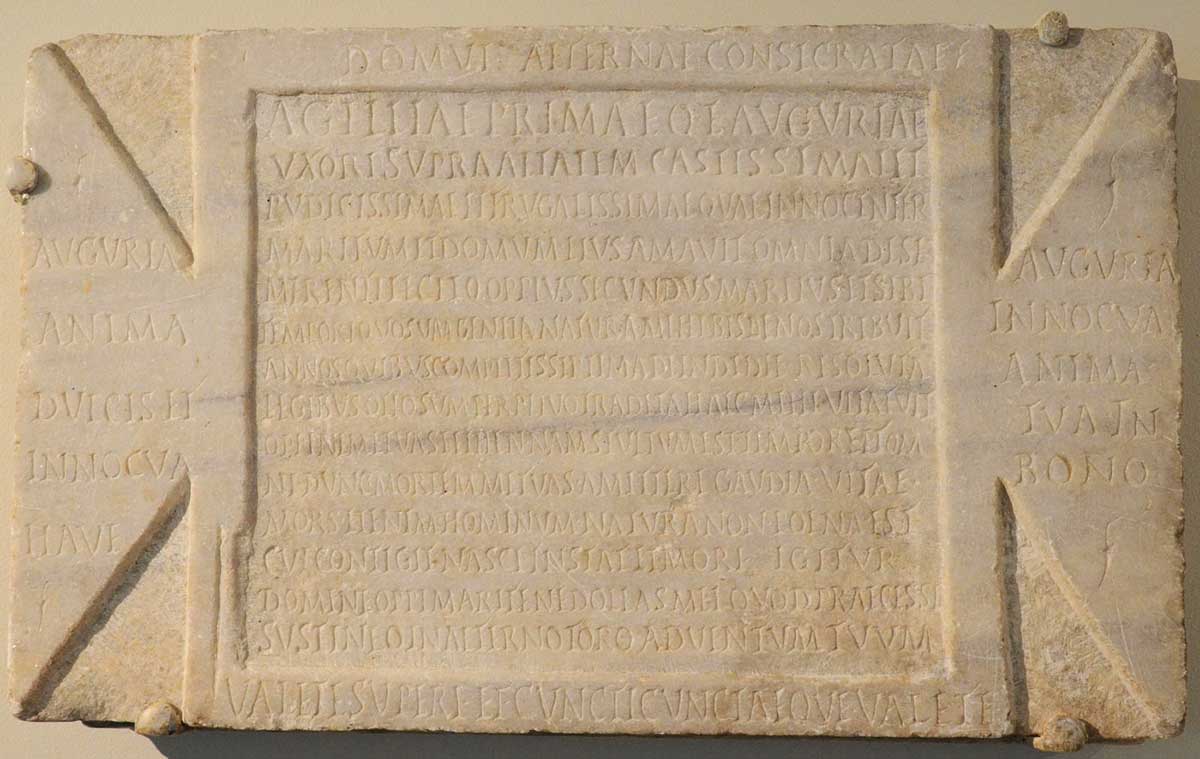

Measurements: Height: 37.0 cm, Width: 60.4 cm, Thickness: 5.4 cm

Material: Marble

Date/Culture: Roman, 2nd – 4th century CE

Provenance: Rome, Italy

Translation

Main Text:

“To the eternal consecrated house

And to Agileia Prima who was also known as Auguria.

Wife beyond eternity; most chaste and modest and frugal who loved

Her husband and his house and all his possessions innocently.

Quintus Oppius Secundus, her husband, made this for the deserving one and for himself.

At the time I was begotten, nature granted me twice ten

years, upon the fulfillment of which, on the seventh day thereafter,

freed of the laws [that bind one to life] I was given over to unending rest.

This life was given to me, [so]

Oppius, do not fear Lethe, for it is foolish to lose joy of life while fearing death at all time.

For death is the nature, not the punishment of mankind; whoever happens to be born, therefore also faces to die.

Master Oppius, husband, do not lament me because I have preceded you

I await your arrival in the eternal marriage bed.

Be well, my survivors, and all other men and women, be well.”

Text on Left side:

“Hail Auguria, a sweet and innocent soul.”

Text on Right side:

“Innocent Auguria, [may] your soul [rest] among the good.”

Description

This inscription is inscribed on a “tabula ansata,” literally a tablet with handles. The stone was set up by Quintus Oppius Secundus for his wife, Agileia Prima, who was also called Auguria (line 2). The text is an interesting example of how elaborate funerary inscriptions could be. Most of the text is written in meter (for example, lines 10 and 11 are complete hexameters while Line 15 presents as a iambic senarius). Moreover, the voice changes in line 7. The first six lines are written in the traditional formulae that can also be seen in other inscription on this wall (who is buried here, and who dedicated the tomb). In line 7, however, Agileia herself takes over. She first informs the reader that she died shortly after her 20th birthday, and then addresses her husband, advising him to not spend the rest of his life mourning her. He is to enjoy his life and she will await his arrival in the afterlife.”Lethe” in line 10 refers to one of the five rivers of Hades. According to Greek mythology, the shades of the dead drank from it in order to forget their earthly lives.

Agileia quotes two ancient works here, the Distichs of Cato in line 10, and two works by Seneca in lines 12 and 13. The Distichs of Cato form a collection of short wisdoms that was used in the Middle Ages to teach Latin and as a moral compass. Even though the sayings are attributed to Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE), who was known for his wisdom, the identity of the author is unknown. The Distichs were probably collected and published in the 3rd or 4th century CE. Nevertheless, is possible that the Distichs also included older sentiments that could date back to the first or second century CE.

The Seneca quotations here are taken from the De Remediis Fortuitorum and Epistle 99.8. The authorship of the former is debated, but, as Robert Newman has pointed out, our inscription can be used as evidence that the work was indeed written by Seneca. It is highly unlikely that two different authors on the same subject would be quoted in such close proximity. The De Remediis Fortuitorum is a dialogue about chance events that cannot be avoided. Many of the instances deal with death in general, and sudden death in particular. Hence, a reference in a funerary context is appropriate.

Unfortunately, the quoted text does not help much with dating the inscription. As mentioned above, the date of the Distichs is unknown. Seneca lived from ca. 4 BCE to 65 CE which provides us with an earliest date, but not a definite latest date. The stone itself has been dated both to the second and fourth century CE. According to Newman, Mrs. Joyce Gordon, a well-regarded epigraphist, dates it to the age of Hadrian (117-138), while the US Epigraphy Project dates it to the fourth.

References

E. Gebhardt-Jaekel, Mors omnibus instat – der Tod steht allen bevor : Die Vorstellungen von Tod, Jenseits und Vergänglichkeit in lateinischen paganen Grabinschriften des Westens, Diss. University of Frankfurt/Main, 2007.

H. Geist, Römische Grabinschriften, Munich: E. Heimeran, 1969, 169; 201,202.

R.J. Newman, “Rediscovering the De Remediis Fortuitorum,” American Journal of Philology 109 (1988), 92-107, 97-98.

C. Hosius, “Inschriftliches zu Seneca und Lucan,” RhM 47 (1892), 462-465.

H.L. Wilson, “Latin Inscriptions at the Johns Hopkins University VI,” American Journal of Philology32 (1911), 166-187, 167-169.

The inscription is described in the US Epigraphy Project hosted by Brown University.