Providing for the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian works from Eton College

Funerary Stela

By Anna Schwarz, Ashley Fiutko Arico, Harrison Ihrig and Sanchita Balachandran

Description

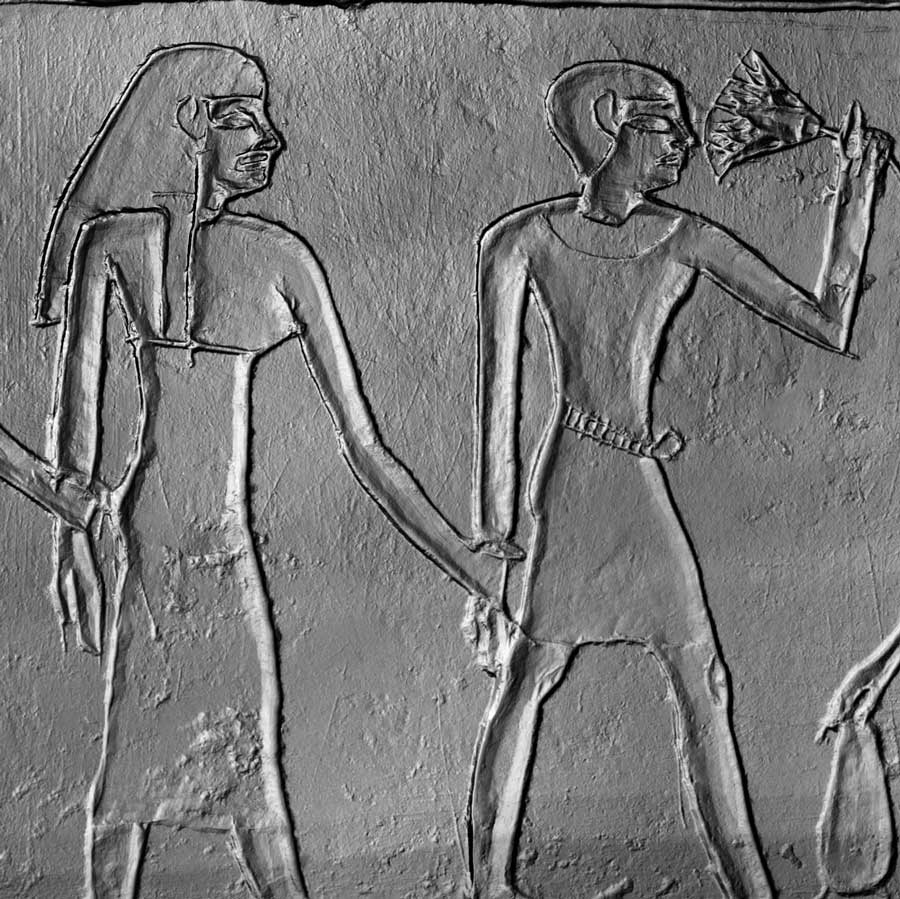

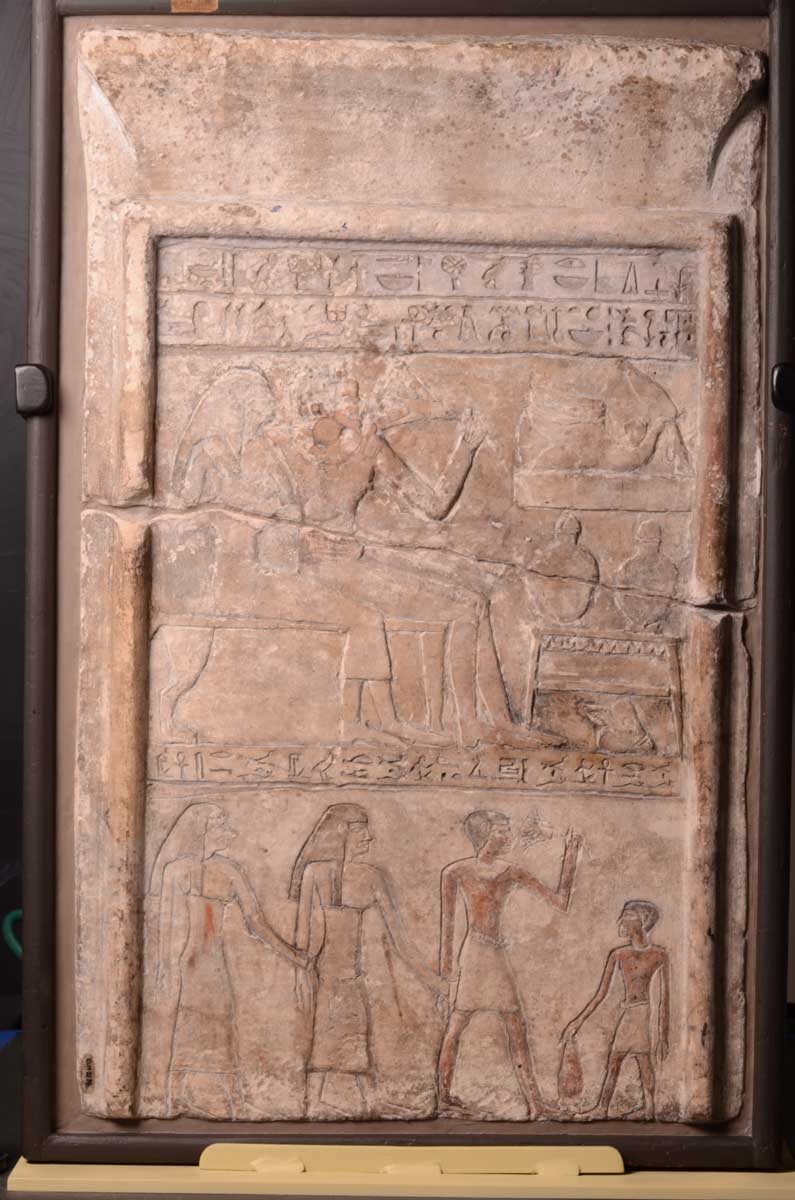

Funerary stelae such as this one enabled those still in the realm of the living to commemorate those that had gone before them, simultaneously providing them with food, drink, and other requirements for the afterlife. This rectangular stela is divided into two registers that are framed by a torus molding with a cavetto cornice at the top. These elements have an architectural inspiration, being found in ancient Egyptian buildings. In the upper register, a man and his wife sit side-by-side embracing as he holds an open lotus flower (a symbol of rebirth) to his nose. The text, written in two rows of hieroglyphs above their heads, gives their names as Inwiaankh(?) and Hepy, and enumerates the types of offerings they desire: bread, beer, oxen, fowl, and “everything that is good and pure.” Some of these customary offerings are illustrated in front of the couple around a low offering table and mat, including the head and foreleg of an ox. In the lower register, more members of the family, identified as his sons and daughters, are shown. Once vibrantly colored, the stela was designed in part to attract visitors who could read the offering formula aloud on behalf of the owners, ensuring their continued access to the goods that it names.

Technical Research

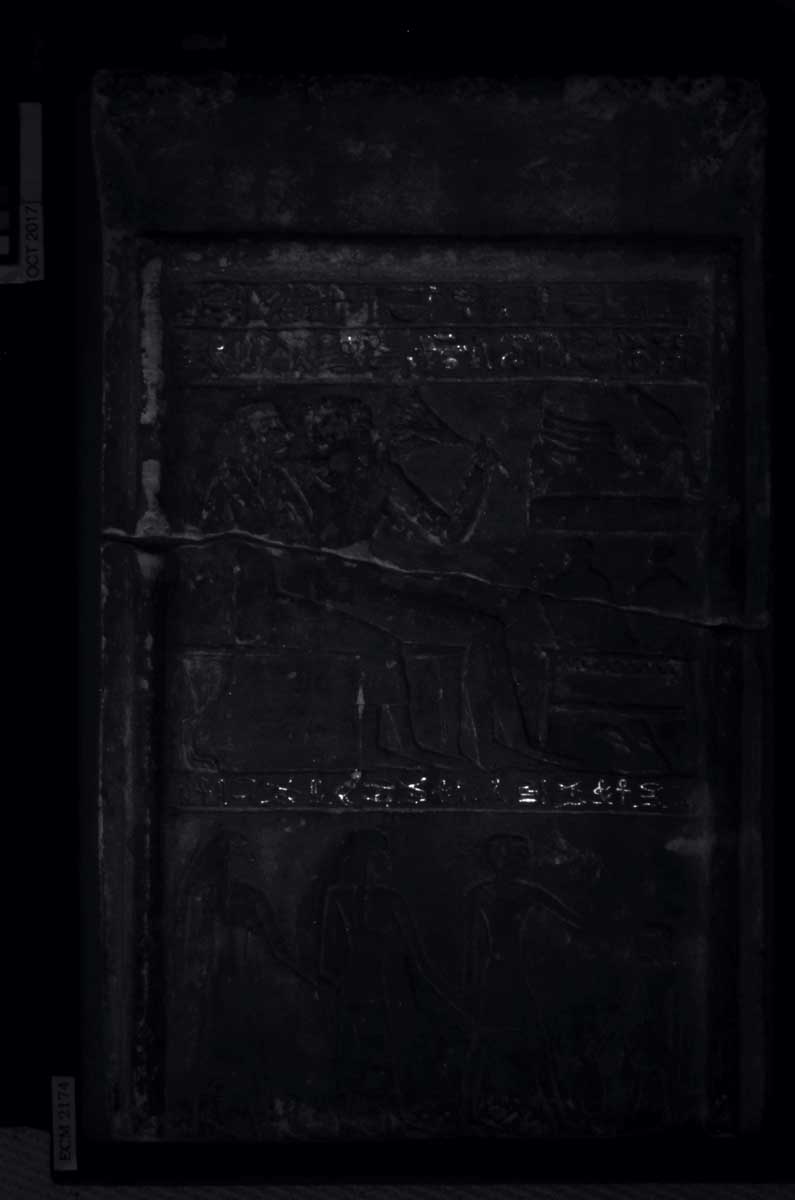

Undergraduate students Harrison Ihrig and Anna Schwarz upon examining the stela under the stereomicroscope suggested that there was a darkened modern coating over the entire surface. Further study and small cleaning tests by Sanchita Balachandran confirmed the presence of a water-based coating that was likely applied on the surface at some time after it was removed from its original context, possibly to ensure that the painted surface remained intact. Over time, however, this coating had discolored and blackened with dirt. Prior to beginning any large-scale cleaning of the stela, it was imaged using multi-band imaging to identify the presence and locations of any ancient pigments and paint layers as well as more recent coatings. One exciting discovery was the presence of the ancient pigment Egyptian blue only in the registers of text. In visible infrared luminescence, even tiny particles of this pigment–which are not otherwise visible–glow brightly, as in the image to the left. Unfortunately, most of this pigment which was pressed into the hieroglyphs, has been lost over time. Infrared reflectography also made it possible to see the presence of painted black criss-crossing lines along the edges of the rounded framing element that were otherwise obscured by the dark coating. X-ray fluorescence examination of the painted surfaces revealed that the stela was likely entirely coated with a calcium based plaster, and the area that now appear red are painted with an iron oxide pigment while the black areas were painted in carbon black. There are traces of other shades of color–for example, in the alternating vertical bands at the top of the stela–but as they are composed of the same elements (primarily iron), it is difficult to reconstruct how they might have once looked.

Studies of the reflectance transformation imaging dataset gathered in 2015 made it possible to see the extensive tool marks and abrasive marks from the process of carving that are still preserved on the stone. With all of the information at hand, it was possible to begin the conservation and cleaning of the stela to return to some of the original balance of the painted surfaces.